We have to know what we know, not what we think we know.

Craig A. Spisak

Director, Acquisition Career Management

Above the door to my office is this expression: “IN GOD WE TRUST—EVERYONE ELSE BRING DATA.”

I didn’t come up with this idea, but I use it a lot. When it comes to talent management and workforce management, one of the biggest challenges we face in the way of data is that we don’t necessarily have a robust data system for talent management. We have historically collected a lot of demographic data. We know the types of degrees our workforce has, the schools they’ve attended, the training they’ve achieved and their work experiences. But we aren’t collecting and capturing much data on competencies. That’s why we tend to do studies and assessments of competencies and skill sets to understand where our skill gaps are and may be in the future.

DO WE HAVE THE RIGHT DATA?

Which raises a question: Have we collected the data we need on the talents of the Army Acquisition Workforce (AAW)? Do we just need to analyze it more completely? Or do we need more data in order to build a better AAW? The answer is D, all of the above.

Obviously, analyzing the data we have is an important aspect of making smart decisions. Too often, people overlook the importance of “knowing what you know” and rely instead on what they think they know. The only way to get people on the same page and heading in the right direction is to have valid, verifiable data that says, “This is why we know what we know.” Otherwise, strategic decisions are likely to be based on gut instinct or opinion. And when strategic decisions are based on gut instinct or opinion, there’s no way to defend them to somebody who suggests that a particular choice is not the right one. That’s why I’ll say it again:

We have to know what we know, not what we think we know.

However, in many cases we don’t have the capacity or access to collect the data we may need. Then we’re stuck doing our best to make inferences when the actual information is too hard to get, unavailable or too expensive to gather.

PUTTING DATA TO WORK

In a perfect world, everyone would have enough time built into their work schedule—and I know that is a very challenging statement—to use something like the Acquisition Workforce Qualification Initiative system to capture competencies. There’s a big difference between the skill sets of a contracting professional who does work in supporting contingency operations and those of one who works in acquiring weapon systems. But when they get their experience and they have the same amount of time and training, they both get the same certification in contracting.

Currently an organization or potential employer can’t see the differences without culling resumes and conducting interviews. There’s no big pool within a management information system that says, “Oh, here are the people who know how to do this, have a particular competency or possess a specific skill set.”

There are a number of places where we need to drill down and get that second-level, third-level and fourth-level information.

THINK GLOBALLY, ACT LOCALLY

What’s the old adage? You can use data to tell any story you want.

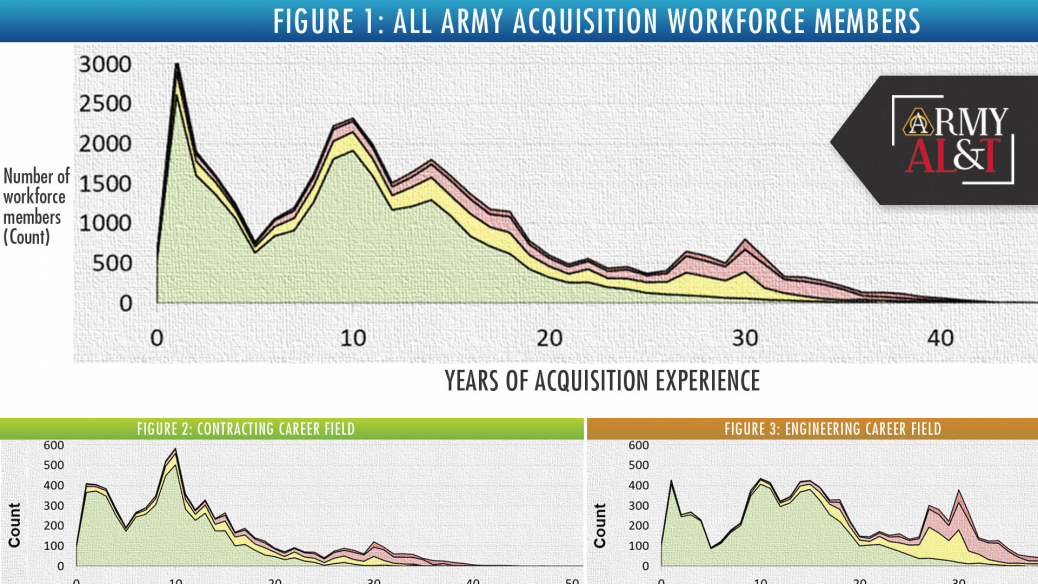

If we look at the workforce in the aggregate, it might seem to have unique characteristics. But if we drill down and only look at the engineering community, for example, we might find something very different. For example, take a look at Figure 1. It shows the aggregate AAW with respect to years of experience. Then look at Figure 2, which shows the years of experience for the contracting community. It generally looks the same as Figure 1. Figure 3 shows the engineering community. Engineers tend to stay in their jobs longer, and many are either eligible for retirement or nearing it.

What’s happening across the acquisition workforce is not necessarily happening to the engineering community. And if we break that down even further—maybe what’s happening at one of our centers of gravity like Aberdeen versus Huntsville—sometimes it’s different from the engineering community at large. You really have to think globally and act locally.

We in the Office of the Director for Acquisition Career Management and the U.S. Army Acquisition Support Center are trying, to the best of our ability, to work with those communities to allow them to help themselves. We are hardworking and dedicated, but we can’t figure out why, as an example, organization X doesn’t have the right skill set or competency for artificial intelligence. We need that organization to step up when a problem arises; there’s currently no way for us to drill down to see if that’s possible. If they see that the problem is caused by a broader issue at the aggregate level, then we here at the Acquisition Support Center can try to help address that through a number of our programs.

But at the local level, we need them to bring that problem forward so we can try to help solve it. It might mean sending somebody to school. It might be developing a local training program. It might be using the Defense Acquisition Workforce Development Fund to hire an intern. There are lots of ways that we can assist.

We have good processes to evaluate and analyze their data, but we don’t typically have their data. We don’t have their insights or knowledge as to what’s going on. For as much effort as we put into strategic communications, I’m still constantly finding somebody who is surprised to learn that we can help them with an issue. Because the information we put out is abundant. It’s pervasive. It’s there for anybody who’s looking for it. Our website, https://asc.army.mil/web/dacm-office/, is one-stop shopping. Almost everything that you could possibly need to know is there.

CONCLUSION

It would be great if everybody had the time in their day to capture all the things that they’re doing to manage their talent and the lessons that they’ve learned, and write them down. But every day brings the next emerging challenge. It’s not because people don’t want to manage their talent or that they’re not dedicated to doing it. But everyone is constantly facing new challenges; it’s a matter of how you prioritize your time and effort.

But when you can take some time and put some thought into writing down what you’ve learned—about competency shortfalls, talent management, prioritizing lessons learned—so that we can populate a number of data sources, it helps everyone, not just you but all those around you. And the people who come behind you.